Super User

So you're cured of Hepatitis C - What next?

So you've made it! SVR12 and you are cured of Hep C. Maybe you battled your insurance company for access to the medications. Maybe you sourced generic medications yourself.

For most patients at this point that's it. It's over. You're cured and Hepatitis C can drift quietly into the past, but there is one group of patients who do need ongoing follow up. That group is the group of patients who have cirrhosis. If this is you please follow the advice below:

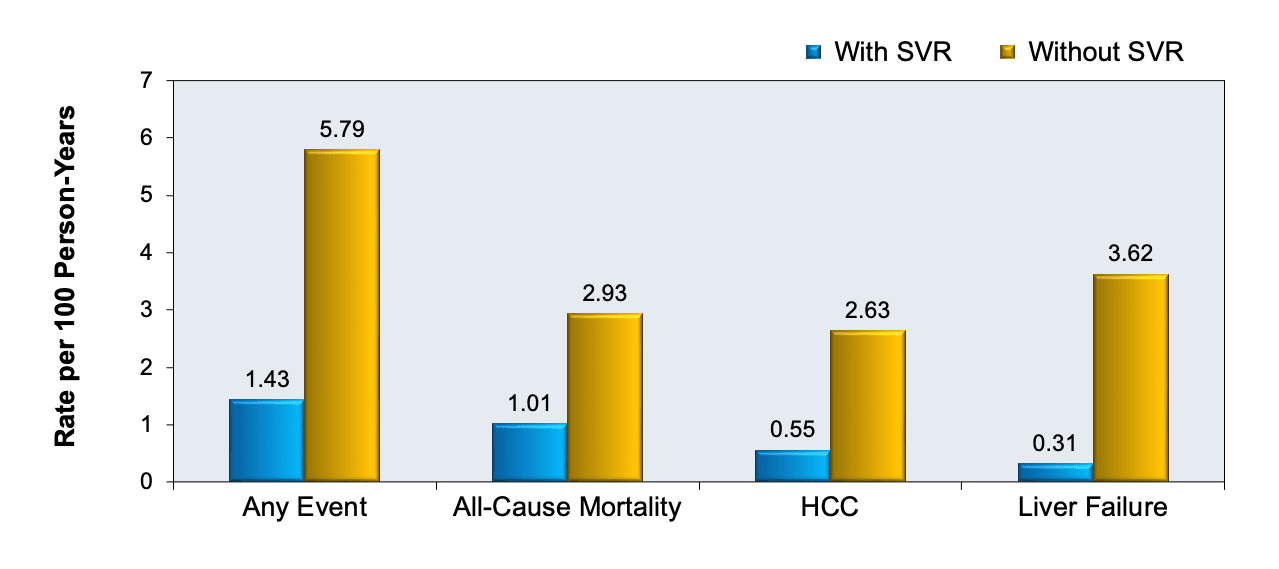

Every 6 months arrange for an ultrasound of your liver and an AlphaFetoProtein (AFP) blood test. This is suggested by both AASLD and EASL because cirrhosis carries an increased risk for the development of HepatoCellularCancer (HCC). Prior to treatment that risk was about 3% per year, and with SVR12 it falls to less than 1% but it does not fall to zero. With any form of cancer early detection allows for early treatment and cure, so keeping an eye out for this issue is a great way to protect your health.

If you look at the impact of SVR you can see quite clearly why treatment is probably the single best thing a patient with Hepatitis C can do for their health.

The Use of TRIPS Flexibilities for the Access to Hepatitis C Treatment

Here is an article from the South Centre in Geneva.

Abstract: In late 2013, a new Hepatitis C treatment called direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) was introduced in the market at unaffordable prices. The eradication of the disease is possible if medicines can be purchased at AFFORDABLE prices within health budgets. IF THIS IS NOT THE CASE, governments should consider the use of the TRIPS flexibilities to facilitate access to the treatment.

This article starts like this:

General Context and Background on the Debate over Access to Medicines

The problem of access to medicines until 2014 was concentrated in developing countries where one third of the world’s population had no access to medicines, while industrial countries, thanks to public (Europe) and private (the United States of America) insurances managed to pay the cost of medicines. Currently the situation in developing countries remains the same but the great novelty, unprecedented, is that the industrialized countries are beginning to have difficulties in ensuring the supply of certain medicines to their citizens. The debate and international negotiations on access to medicines began in 1995 with the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), at the end of the Uruguay Round, and the generalization of the mandatory use of patents for pharmacological products for all WTO member countries (currently totalling 164).

And in the middle find this:

Pharmaceutical innovation has significantly diminished in recent years

According to the data published by the French review Prescrire in recent years, we find that the number of medicines that constant “an important therapeutic advance” introduced into the French market in the last 10 years are not more than 14 per year; furthermore, innovation appears to be diminishing, as the maximum number of 14 is significantly higher than the average number of yearly therapeutic advances over the past decade:

- 2007: 14 products

- 2008: 6 products

- 2009: 3 products

- 2010: 3 products

- 2011: 3 products

- 2012: 3 products

- 2013: 6 products

- 2014: 5 products

- 2015: 3 products

- 2016: 1 products

You can read the full article here: https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PB54_The-Use-of-TRIPS-Flexibilities-for-the-Access-to-Hepatitis-C-Treatment_EN.pdf but, in short, we are in a "Houston we have a problem" kind of a situation. Despite very high prices, we are seeing very little innovation.

Understanding AFP (Alpha Feto Protein)

AFP is short for Alpha FetoProtein.

As the "feto" in the name suggests this is a protein we see in a fetus. In adults we switch off the genes that produce it so we don't see much (usually <12 units)

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) represents a loss of control over liver cell growth. These liver cells tend to become more primitive, like the liver cells in a fetus. What often happens is that the genes that produce AFP get switched on again, so instead of seeing <12 units of AFP we see more.

In pragmatic terms:

Most patients will have an AFP <12 and will not have HCC

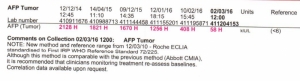

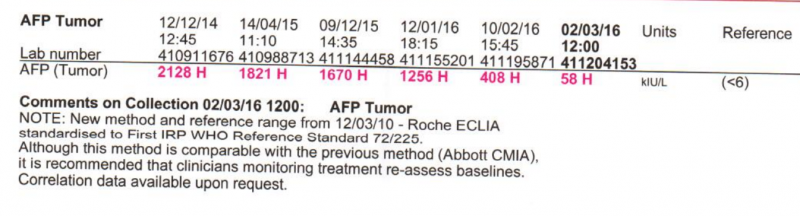

Some cirrhotic patients will have a slightly elevated AFP in the range 12-24, despite not having HCC. We invariably see this fall during and after treatment. Sitting on my desk I have these results from a cirrhotic patient who is now at SVR

Most, but not all, patients who develop HCC will have a detectable rise of AFP, usually to a level of over 100

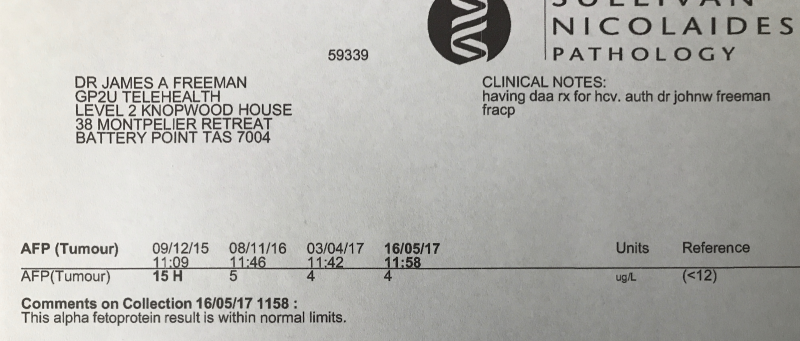

Here is a patient who had HCC in whom we treated the HCV and the HCC (with Sorafanib). Notice both the fall in AFP and the fact this lab uses <6 rather than <12 as the cutoff

Please note this: while most HCC expresses AFP and therefore can be detected by an AFP blood test it is possible to have HCC with a normal AFP. Rare but possible. High risk patients with cirrhosis should have 6 monthly screening with U/S (or CT or MRI)

Also note that if you have had HCV but have not developed cirrhosis then your risk of HCC is almost exactly the same as the general population. It happens, but it is rare. AFP screening is more than adequate. If you want to have a look use U/S or MRI as a CT carries about a 1:1000 risk of giving you a cancer (it might be a little lower than this but is does carry a real risk).

Are The New Hepatitis C Treatments Poisonous?

So today, on the chat a patient mentioned "My doctor here is scaring me from getting treated. He is tell that the treatment can be poisonous."

5 years ago this doctor would have been correct, in fact, I used to think the same, going so far as to say "The treatment is worse than the disease".

So what has changed?

5 years ago the mainstay of treatment was PEG Interferon injections and Ribavirin tablets. Both of these drugs have a lot of side effects and with a 1 year treatment required to deliver a 50% chance of cure it's easy to understand why the treatment was not popular. The side effect list looked like this:

- Flu-like (headache, fatigue, fever, chills, muscle ache)

- Arthritis-like pain in back, joints

- Gastrointestinal (low appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea)

- Low blood cell counts

- Depression

- Insomnia

- Hair loss

- And lots more...

All that changed in 2013 when a drug called Sovaldi® (Sofosbuvir) reached the market. This was rapidly followed by other drugs like Harvoni®, Viekira®, Zepatier®, Epclusa®, Vosevii® and Mavyret® (Maviret® in some countries). With these new drugs what we got was this:

- A typical 3 month treatment period

- Taking 1 (or a few) tablets a day

- Where there were minimal side effects (and the average patient actually felt better on treatment rather than worse)

- And where the treatment delivers a 95%+ chance of cure at the end

To tell you the truth it all sounded a bit too good to be true, but, having treated 3000 patients myself, and seen the results repeated by doctors around the world there is no doubt we have some really good solutions to curing Hepatitis C.

Getting access to these new medications can be a bit of a problem in some countries due to the cost, but affordable generics are available and they deliver the same results at a small fraction of the originator pricing. So, if you have Hep C, and would like to get back to better, do yourself a favour and look into getting treated. If you local doctor can't help, we can help with both your prescription and getting access to the medication.

Why Does Hepatitis C Treatment Fail Sometimes?

Here is a question I was asked: I am a biochemist myself and studied virology many years ago. Unlike HIV, HEP C doesn’t seem to reside in reservoirs. So looking at your SVR rates they are impressive but could you maybe give me a high level reason why treatment fails? Apart from reinfection where could the virus hide? I have bought 20 weeks worth of meds and now I am on week 18. Was undetectable at week 3 so by the end of treatment I will have kept it at bay for a further 17 weeks. They should surely be enough to eradicate it?

Here's the answer.

There are multiple reasons treatment fails. They can broadly be divided into

- Viral Vector Factors

- Host Factors

- Drug Factors

- Resistance and Selective Pressure

Viral Vector Factors

The genetic code of the Hepatitis C virus is single-stranded RNA. Unlike DNA, which has two mirror image strands that deliver error checking, HCV RNA is duplicated like this:

- First, the RNA polymerase makes a mirror image (non-sense) strand of RNA from the viral RNA.

- Then it uses this to make another mirror image (sense) strand.

There is no error checking and 50% of the RNA produced is non-sense. This process is inefficient and error-prone. Every time the RNA duplicates there is about a 1:1000-1:10,000 chance the new RNA copy is inaccurate. Mostly this means it does not work properly, but sometimes it confers resistance. The so-called “wild type” is the most common form of the virus simply because it duplicates itself better than any other variants, however, some of the resistant variants are known as “fit mutants” because these RAVs (Resistance Associated Variants) reproduce almost as well as the wild type. These are the problem children.

Within one person there are a whole range of similar, but slightly different, variants of HCV RNA – this is why it is called a quasi-species.

The RNA itself is used to code a number of proteins of which the NS3/4A, NS5A and NS5B proteins form the 3 different targets for our drugs. The drugs work in a key/lock fashion where the drug is the key and the protein is the lock. The drug keys occupy a vital space in the protein which needs to be vacant for the protein to do its job. Small changes to these proteins change the lock so the key does not fit as well. Small changes to the RNA genetic sequence underlie these changes to the proteins.

Most of our drugs are what is known as competitive inhibitors, so they compete with usual substrate (the thing that normally fits the lock) and therefore need to be above a certain concentration to do their job. This concentration is known as the EC50 (Effective Concentration for 50% of the maximal inhibition). Sofosbuvir works on the NS5B RNA Polymerase protein. The reason it is so good is that this protein is the engine room making new viral RNA and Sofosbuvir is a suicide inhibitor – it binds permanently to the active site so can’t then be displaced when the concentration falls.

The different genotypes of HCV represent similar (but different) RNA sequences. Some genotypes of the virus are naturally resistant to some of the drugs. For example, Ledipasvir does not work well on Genotypes 2 and 3 because the NS5A protein target is a poor fit.

Logically you’d expect the longer you’ve had the virus, and the higher the viral load the more duplication cycles have happened and the greater the chance of resistance. There are hints that this is the case, but no solid proof.

What we do know to be true is that to be resistant to 1 drug is not that hard, but to be resistant to 2 (or more) is much harder. This relates to the 1:1000 probability of a mutation. To get one (on a single strand of viral RNA is 1:1000) but to get 2 is 1:1000 x 1:1000 = 1:1,000,000 and to get 3 it is 1: 1,000,000,000.

HIV is another RNA virus where we have seen this. When we only had one drug resistance happened quite quickly, with 2 drugs it took years, and with current 3+ drug combinations, resistance and virological breakthrough is rare.

Finally, HCV is very infectious. We know from monkey experiments that just 10 virus particles (virions) injected gives a 50% infection probability, and 100 virions deliver a near 100% infection probability. To get rid of this beast we need to kill it down to very nearly the last virion. It’s truly remarkable we can do this.

Host Factors

There is a disease called pernicious anaemia. Patients get this because they cannot absorb the small drug-like molecule vitamin B12. Similarly, some patients do not absorb some drugs very well. For the Hepatitis C DAAs, if we look at the blood levels of a group of patients, the patient with the highest levels may be absorbing 2-10x as much as the patient with the lowest levels. Ledipasvir and Velpatasvir are more problematic in this realm than Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir.

While the drugs do much of the work, our immune systems still play a role in mopping up the stragglers. We know that 25% of people can clear the virus themselves, and obviously they have strong anti-HCV immune systems. We also know some people run low viral loads – they have moderately strong anti-HCV immune systems. People with high viral loads have weak anti-HCV systems but this is not as bad as you might think. Firstly the virus does not “eat” much so just letting it do its thing causes very little harm (less than fighting it all the time but not quite winning) and with our current drugs people with high viral loads enjoy similar cure rates, albeit sometimes requiring slightly longer treatment.

Unlike HIV there are no known “reservoirs” where HCV can hide, although that said there kind of are. By "kind of are" I’m referring to damaged cirrhotic liver and probably HCC. With cirrhosis parts of the liver are replaced by scar tissue. This tissue has very little blood supply meaning that a drug circulating in the blood does not reach very high levels in this tissue due to the distance it has to diffuse. This makes cirrhotic patients harder to cure, unless we transplant them when, despite the immunosuppression, they are easy to cure. We also see patients with HCC as being harder to cure. This probably relates to the background cirrhosis, but could also relate to the fact that cancer cells refuse to obey apoptosis (die now) signals they get from the immune system.

Drug Factors

As mentioned earlier some drug keys are a poor fit for the protein locks of certain genotypes. This can be a real problem when a patient is co-infected with 2 types of HCV – say genotype 1 and genotype 2. The genotype 1 will be dominant so that patient may get their genotype reported as simply genotype 1, but with ledipasvir not working well on genotype 2, if this patient is treated with Harvoni they will clear the GT1, but relapse with GT2.

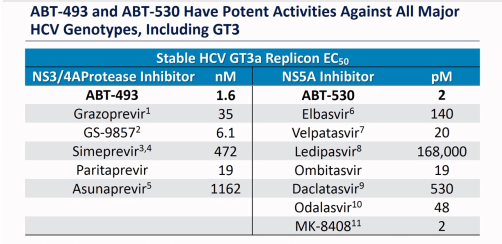

Different drugs have different potencies. A drug with a high potency has a low EC50, and a drug with a low potency has a high EC50. For the drug to work it needs to remain above the EC50 throughout the day, otherwise there are times when it is below the level required to contain viral replication. Here is a table for GT3.

ABT-493 and ABT-530 are the Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir in Mavyret (Maviret). GS-9857 is the Voxilaprevir in Vosevii and MK-8408 was Ruzasvir (now discontinued).

As mentioned before, some patients do not absorb some drugs as well as other patients so, even if properly dosed they may wander below the critical drug levels.

Some patients do not take their medication every day, and this results in blood levels potentially falling below what is required.

Some medications, supplements and foods interfere with the absorption of the DAAs. Sometimes this increases the blood levels, which, although it leads to more side effects, does not compromise treatment. However, sometimes medications (such as antacids with Harvoni and Epclusa) decrease the blood levels of the drugs and this can lead to treatment failure.

The duration of treatment is vital. The disappearance of the virus follows a pattern of exponential decay meaning (for example) on day 1 we have ½ the virus, day 2 we have ½ of that ½ ie ¼ and on day 3 we have ⅛. Now when we remember we need to go from zillions to < 10 actual viruses we can see that this takes time. Although it saves money we see a lot more GT1 Harvoni failures who took 8 weeks than those who took 12 weeks. The extra weeks are a form of insurance. For almost anyone who achieves SVR at some point we are pouring medication into a body that no longer harbours HCV – we have to overtreat to make sure, and we need to pick a “one size fits all” duration.

Another reason duration is vital relates to the half-life of a viral replicon. This is several weeks. If we don’t treat for long enough a replicon can be suppressed from working, but remove the drugs and it can recover. We need to display no mercy and keep kicking it while it is down until there is no chance it can recover.

Just a quick note on Ribavirin. The log kill on Sofosbuvir is 4.5 meaning it will kill 31,999/32,000. For the NS3/4A and NS5A agents is more like log 3 meaning they will kill 999/1000. Ribavirin is weak in comparison with a log kill of 0.5 meaning it will kill only 2/3 but that may just come in handy mopping up the stragglers. Of note is that Ribavirin is not a DAA – it is a fake letter U in the genetic alphabet so not prone to the same resistance mechanisms as the DAAs.

Resistance and Selective Pressure

We know from HIV that a patient who has a detectable viral load is at risk of a virological breakthrough. Why is that?

When we start treatment, pretty much all the easy to kill virus in the quasi-species is rapidly killed off, however not all of it is. Some of the variants will be partially resistant and the drugs are exerting a selective pressure. Now, despite the fact these RAVs may not be as fit as the wild-type, we have removed the competition. If one of these RAVs “lucks out” and mutates in a way that makes it either more resistant to the current drugs, or more resistant to (the usually missing) 3rd drug on a 3rd target we have a “Houston, we have a problem” kind of a moment.

Wrapping Up

Considering the ask – kill down to the last 10 virions - it’s truly remarkable that Sofosbuvir alone can deliver a ~66% cure rate. We know that adding in an NS5A agent improves that to ~95%. We also see that highly potent NS3/4A+NS5A combinations like Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir can also kick ass, but here is a lesson from HIV. 3 drugs work better than 2. This is particularly relevant for patients being offered G/P for retreatment. The expected SVR is “only” 90% but if it was me… I’d add in the best NS5B ever invented (Sofosbuvir) to the best NS3/4A and the best NS5B.

Buy Generic Harvoni

When the drug Harvoni was announced back in 2014, it was very welcome news for Hepatitis C sufferers around the world. Finally, a single pill treatment for this notorious disease was available. Taken once daily for just 12 weeks, it cured 95% of patients with minimal side effects. Unfortunately, the excitement lasted only until the new drug's price was announced, $94,000 USD. This meant that patients had to be either super rich or eligible for insurance coverage and unfortunately, 90% of patients were neither. Because of Harvoni's astronomical price tag, many insurance companies refused to cover patients unless they were in a very late disease stage, defined as severe liver fibrosis (i.e. F3 or F4). This left 90% of patients unable to access brand name (originator) Harvoni and having to look for overseas online sellers who supply generic Harvoni. But how can a patient safely access generic Harvoni on the internet that is of the same quality as brand name Harvoni? If you take the following 5 factors into consideration, you will be able to find a trustworthy and affordable online supplier.

1. Watching out for Scammers

We hear a lot about scam websites on the Internet, especially foreign sites in developing countries. So how can you make sure you don't get taken? To avoid scam artists, patients need to do a bit of research to separate honest medication suppliers from scammers. Google is your friend here - it's a great tool for discovering information. You should search Google for the website's name, the name of its founder (if available), and find out about their track record. If you find none or multiple bad reviews, definitely avoid that supplier as it will be quite risky. Here's a quick guide.

Additionally, if media outlets (such as TV networks, newspapers, or reputable websites) publish good or bad information about the website you're researching, this will give you excellent insights about it. It's worth noting that here has been a lot of positive scientific and mainstream media coverage on FixHepC and its founder, Dr. James Freeman, such as in WebMD, Healthline, The Lancet Medical Journal, BBC Newsnight, Medscape, The Sydney Morning Herald, and many others. Here is a BBC Newsnight video investigation of one of the early FixHepC patients.

2. Verifying the Quality of the Harvoni Generic

Just like with any other product, there are good and bad quality generic medications. So how to ensure the quality of the Harvoni generic you buy? There are two factors that decide the quality of all generic medications: Bioequivalence and GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice).

Bioequivalence:

A generic drug is considered bioequivalent to its brand name counterpart if their pharmacological effects are exactly the same. The easiest way to ensure this is when the generic manufacturer is granted a license by the originator company to produce the drug. This license notionally guarantees that both the generic and originator drugs are exactly the same however the Gold Standard is a thing called bioequivalence. This is explained in detail in this post.

At FixHepC we only use licensed medications from manufacturers that have proven bioequivalence.

GMP:

Good Manufacturing Practice certificates, as the name implies, are issued by the US FDA and EMA (European Medicines Agency) when a drug manufacturer meets all the requirements for highest quality mass production of pharmaceuticals. Needless to say, you should choose manufacturers that were awarded this certificate. GMP is the only thing that guarantees the latest batch of medication meets the same high quality standards as the batch that passed bioequivalence testing.

3. Avoiding Fake Drugs

Unfortunately, fake drugs are a real problem in many developing countries, such as India and Bangladesh, and almost all generic Hepatitis C drugs are sourced from there. So how can you make sure that you’re buying authentic generic Harvoni® (or other Hep C generics like Epclusa®, Sofosbuvir®, and Daclatasvir®) and not fall victim to dishonest or incompetent online suppliers? The answer is that you have to check the Supply Chain Integrity of the online seller, but that is easier said than done. Here is a primer on how to do that: https://fixhepc.com/supply-chain-integrity.html

4. Getting Guaranteed Delivery

Patients in most countries are not sure if they can legally import generic medications from abroad, and are worried that the medications they will pay for may be stopped by border customs and confiscated. In some countries, importing 3 months worth of personal medications is perfectly legal, as long as a doctor’s prescription is attached with the medications. However in some other countries, this is a gray area, and delivery is not guaranteed. It requires expertise by the shipper and learning how to abide by these countries laws and preparing the required paperwork. To make sure that you will not lose your medicines package due to an overzealous customs officer, only buy from suppliers who offer guaranteed delivery or 100% of your money back. It’s rare to find an overseas medicines supplier who would take that risk and provide that guarantee. To give patients peace of mind, FixHepC does just that, and they are able to do it because they have learned over 6 years how to deliver drugs successfully all over the world.

5. Getting a Prescription and Medical Support

For one reason or another, many patients are not able to get a prescription for generic Harvoni from their doctor, so how can they get one? Also, many doctors will not monitor patients if they didn’t write their prescription, so what if you need medical support during treatment? It’s inconceivable, you may say, that online drug suppliers would provide such services, after all they are not doctors. Well, you would be right, except in the case of FixHepC. FixHepC was founded and is managed by a licensed Australian doctor, Dr. James Freeman, who is is arguably a leading expert in the field of Hepatitis C treatment. If patients have any questions during or after treatment, they can pose them for free on the site’s live chat platform and get them answered by one of FixHepC’s excellent doctors, or they can post them to the FixHepC Forum and get them answered directly by people who have been there and done that. If patients need a prescription for Harvoni, they can get one by booking a video appointment at the Australian online doctor service GP2U (Australian prescriptions can be legally used to import personal medicines into the vast majority of countries, including the US). The cost for this service is 70 USD. Follow up can be through further video appointments.

Conclusion

You don’t have to be really rich or wait many years and get very sick before somebody agrees to treat you. You owe to yourself and to your family to take matters into your own hands and to get treated and cured now. Visit FixHepC to learn how to access high-quality generic Harvoni for only $950 USD all inclusive and rediscover what it feels like to be well again.

Hep C generics set to be released in the USA in 2019!

The good news is that Gilead plans to launch generic versions of Harvoni and Epclusa in the USA. The bad news is the $24,000 USD price tag. Although this price is substantially lower than list price, the reality is that the VA negotiated a $25,000 price nearly a year ago, so the payers have been seeing this pricing for a while. The biggest bit of upside is that patients could save up to $2500 in out of pocket costs and that's got to be a good thing. Here is the full press release...

FOSTER CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Sep. 24, 2018-- Gilead Sciences, Inc.(NASDAQ: GILD) announced today plans to launch authorized generic versions of Epclusa® (sofosbuvir 400mg/velpatasvir 100mg) and Harvoni® (ledipasvir 90mg/sofosbuvir 400mg), Gilead’s leading treatments for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV), in the United States, through a newly created subsidiary, Asegua Therapeutics LLC. The authorized generics will launch at a list price of $24,000 for the most common course of therapy and will be available in January 2019.

Since the launch of Gilead’s first HCV medication in 2013, the average price paid for each bottle of medicine in the United States has decreased by more than 60 percent off of the public list prices, across health insurers and government payers. Due to the complexity and structure of the U.S. healthcare system, however, these discounts provided by Gilead may not always translate into lower costs for patients. Further, existing contracts, together with laws associated with government pricing policies, make it challenging to quickly lower a product’s list price once it is on the market.

The authorized generics are priced to more closely reflect the discounts that health insurers and government payers receive today. Insurers will have the choice of offering either the authorized generics or the branded medications for both Epclusa and Harvoni. In the Medicare Part D setting, the authorized generics could save patients up to $2,500 in out-of-pocket costs per course of therapy. The authorized generics will also offer substantial savings to state managed Medicaid plans that do not currently benefit from negotiated rebates and that represent a significant number of people in need, potentially opening up access to our medications to beneficiaries who were previously denied coverage.

“Launching these authorized generics is the best solution available to us today to quickly introduce a lower-priced alternative to our HCV medications without significant disruption to the healthcare system and our business,” said John F. Milligan, PhD, President and Chief Executive Officer, Gilead Sciences. “This launch also will hopefully help increase transparency by more closely aligning our medications’ list prices with their cost. Our ultimate goal is to lower the list price of Epclusa – a medication we believe is of great importance given its clinical profile across genotypes – and Harvoni. We are committed to working with all of our partners in the healthcare system to help enable list price reductions of our HCV medications and find better solutions to reduce patients’ out-of-pocket costs.”

Beyond the company’s efforts to reduce patient costs, Gilead is continuing to pursue innovative collaborations and long-term financing models, such as a potential subscription model, that could not only expand access, but aim to eliminate HCV in the United States and around the world.

Why me? Why do I have Hepatitis C?

The stigma and stereotype associated with Hepatitis C says "you only get that from IV drug use". While you certainly can get it from IV drug use, the majority of my Baby Boomer patients didn't. How do I know? Well, of course, I can't know for sure how anybody caught any communicable disease, but when talking to the 3000+ patients I've helped access affordable generic medication there is a recurrent theme. That theme is "Hey doc, I never did drugs, I don't have any tattoos, and I've never had a blood transfusion, so how did I get HCV?" That led me to look for the answer. The real answer, not the stereotype.

The short answer is the medical or dental profession probably gave it to you, but how do I know that?

Well, for a start, we know the disease requires blood-blood contact for transmission and, outside of IVDU, tattoos and blood transfusions most of us don't share our blood with friends. So for people who have the disease, but don't have these risk factors, what other blood-blood exposures did they have? The answer to that is clear, they had two distinct exposure risks:

- Doctors giving vaccinations using reusable glass syringes, reusable needles, and multi-dose vials and jet guns for vaccinations.

- Dentists drilling and scraping away at damaged teeth using reusable tools.

Nowadays with disposable everything, it's easy to forget what medicine looked like in the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s and (believe it or not) the early 90s.

As a young child in the 60s I followed my father around. He worked in Intensive care and I got to play with all sorts of cool stuff. Glass syringes, reusable needles, liquid mercury from the blood pressure machines (shudder). My father and the other staff routinely got blood all over their neatly pressed white lab coats with barely a glove or facemask to be seen. Surgeons used that stuff, but not the doctors and nurses in the rest of the medical world.

I was immunized several times in a gymnasium line up with all my school friends. It was a wham bam thank you ma'am type thing. I thought the jet gun was nifty as there was no needle but discovered it hurt more. As a medical student in the 80s I was aware of HIV but the notion of universal precautions was still a decade in the future. If we got blood on our hands we just washed it off. The world was very different and the acronym OH&S barely existed.

Here are some timelines:

400 B.C. Campaign Jaundice: Hippocrates (yes, the Hippocratic oath guy) described a condition he called “epidemic jaundice.”

8th century A.D.: Pope Zacharias quarantined men and horses with jaundice. This was meant to control the spread of the disease.

1861-1865: More than 40,000 cases of jaundice were recorded in the Union Army during the Civil War.

1942-1945 Hepatitis and World War II: Approximately 182,383 US service members were hospitalized for hepatitis during World War II. The disease was contracted in two different ways. An epidemic of hepatitis broke out among many service members who were vaccinated against yellow fever. The source of the infection was traced to the serum that was used in the vaccine. A different form of hepatitis, acute hepatitis, was found among soldiers who had received blood transfusions.

1951: Rothauser produced the first injection-molded syringes made of polypropylene, a plastic that can be heat-sterilized.

1956: New Zealand inventor Colin Murdoch was granted New Zealand and Australian patents for a disposable plastic syringe, it will catch on but will take time.

1964: Ansell manufactures the first disposable latex medical glove based on the production technique for making condoms, but universal use (as part of universal precautions) will take close to 3 decades to catch on.

1965: The hepatitis B virus was discovered by Dr. Baruch Blumberg.

1973: The hepatitis A virus was discovered at the National Institutes of Health by a team led by Steven Feinstone.

1973: Cases of hepatitis not caused by either hepatitis A or hepatitis B come to be called "non A, non B hepatitis".

1989: Hepatitis C virus (previously known as non A, non B) is discovered by scientists at a California biotechnology company called Chiron.

1991: A test for Hepatitis C in the blood supply becomes available.

1992: The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OHSA) published its Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Around this time, there was increased awareness regarding HIV, and OHSA implemented the rule to protect workers who would come in contact with bodily fluids. OSHA’s standard required employers to provide personal protective equipment, including disposable gloves, to these workers.

So, we know that Baby Boomers are more at risk of Hepatitis C than any other group? Why? It's actually pretty simple.

Some of the soldiers that returned to the USA from WWII came back with Hepatitis C. Poor medical hygiene spread it, and this spread was almost certainly by vaccination in the 1950s, NOT by IVDU in the 1960s and 1970s. Nice theory, but how can we be sure? One word - genomics. Here is the study, published in the most prestigious journal in the world "The Lancet".

Abstract here: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099%2816%2900124-9/fulltext

Full text here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5245154/

Here it is in plain English, thanks to Sheryl Ubelacker from The Canadian Press.

Canadian researchers have determined the peak of the hepatitis C epidemic in North America occurred about 15 years earlier than previously believed, suggesting it wasn’t youthful indiscretions that put baby boomers at a high risk for the disease.

It was long thought that boomers who were infected with the blood-borne virus likely contracted the disease in their late teens or early 20s, due to such risky behaviours as IV drug use or sexual experimentation.

But a study by B.C. researchers found the peak of the hepatitis C epidemic occurred about 1950, when many baby boomers were young children and had plateaued by 1960 — well before the zenith of injection drug use at the end of that decade.

The oldest of the baby boomers were just 5 years old at the peak of the epidemic, the researchers say.

“The spread of hepatitis C in North America occurred at least 15 years earlier than it was suspected before, and if that is the case, the baby boomer epidemic ... cannot be explained by behavioral indiscretions on the part of the baby boomers,” said co-investigator Dr. Julio Montaner, director of the BC Centre of Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

“We suspect that this is more likely attributable to medical practices at the time,” said Montaner, explaining that hepatitis C hadn’t yet been identified and injections and blood transfusions were given employing reusable glass-tube syringes and metal needles, which were subject to contamination despite boiling.

“The baby boomers in North America ought to be offered hepatitis C screening,” he said, “not because they did anything wrong but because they are baby boomers, and so they were alive at a time in which the standard of care was such that we are all potentially at risk of having contracted hepatitis C.”

If you or a loved one have Hepatitis C, but can't get access to insurance-funded treatment, then maybe getting cured with generic HCV medication is worth a thought. Visit our home page to learn more about generic hepatitis C treatment.

Cabozantinib delivers hope for patients with HCC failing Sorafanib

For patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) the options are limited. Caught early enough RadioFrequency Ablation (RFC), TransArterial ChemoEmbolisation (TACE) or surgical resection can potentially be curative. For some patients with advanced disease a liver transplant may be an option, but what about everyone else?

Up until recently, Sorafanib was the mainstay of treatment and the only real option to slow down the progression of the HCC and give patients some extra months or years of time. Nivolumab (Opdivo) appeared in 2017 but remains prohibitively expensive for most patients.

A couple of months ago the New England Journal of Medicine published the Phase 3 results for Cabozantinib which has been shown to work where patients are failing Sorafenib.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1717002

Although it's not a cure it can add some precious time. While it is anecdotal, back in 2015, I had a patient who was failing Sorafenib and was rejected from this very trial having been fully worked up. He was shattered and asked for help. Given this drug was, at the time, very experimental we went through an extensive informed consent process, including enlisting the assistance of his oncologist who said "We really don't have much to lose..." As it turned out he did very well on the Cabozantinib and got 2 extra years of good quality life.

It's not a cure, but it does provide cause for hope, as we inch ever closer to more effective treatments for HCC.

U=U - Undetectable = Untransmissable

Strictly speaking, this relates to HIV but it also applies the Hepatitis C.

Undetectable = Untransmissable

Get tested, get treated, get cured!